The Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO have released their fourth biennial State of the Climate Report, reports The Conversation.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO have released their fourth biennial State of the Climate Report, reports The Conversation.

STATE OF THE CLIMATE 2016 provides an update on the changes and long-term trends in Australia’s climate. The report’s observations are based on the extensive climate monitoring capability and programs of CSIRO and the Bureau, which provide a detailed picture of variability and trends in Australia’s marine and terrestrial climates. The science underpinning State of the Climate informs impact assessment and planning across all sectors of the economy and the environment.

One of the report’s key observations is carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere. A key component of global CO₂ monitoring is the joint Bureau and CSIRO atmospheric monitoring station in Cape Grim, Tasmania, one of three premier global baseline monitoring stations in the world, along with Mauna Loa in Hawaii and Alert in Nunavut, Canada.

CO₂ concentrations at Cape Grim passed through 400 parts per million for the first time in May 2016, and global concentrations are now at their highest levels in the past two million years.

It takes time for the climate system to warm in response to increases in greenhouse gases, and the historical emissions over the past century have locked in some warming over the next two decades, regardless of any changes we might make to global emissions in that period. Current and future global emissions will, however, make a difference to the rate and degree of climate change in the second half of the 21st century.

State of the Climate focuses on current climate trends that are likely to continue into the near future. This acknowledges that climate change is happening now, and that we will be required to adapt to changes during the next 30 years.

While natural variability continues to play a large role in Australia’s climate, some long-term trends are apparent. The terrestrial climate has warmed by around 1℃ since 1910, with an accompanying increase in the duration, frequency and intensity of extreme heat events across large parts of Australia. There has been an increase in extreme fire weather, and a lengthening of the fire season in most fire-prone regions since the 1970s.

Observations also show that atmospheric circulation changes in the Southern Hemisphere have led to an average reduction in rainfall across parts of southern Australia.

In particular, May–July rainfall has reduced by around 19% since 1970 in the southwest of Australia. There has been a decline of around 11% since the mid-1990s in April–October rainfall in the continental southeast. Southeast Australia has had below-average rainfall in 16 of the April–October periods since 1997.

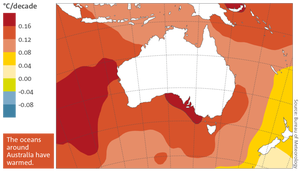

Australia’s oceans have also warmed, with sea surface temperature increases closely matching those experienced on land. This warming affects both the marine environment and Australia’s terrestrial climate, due to the large influence of surrounding oceans on our weather systems. Sea levels have risen around Australia, which has the potential to amplify the effects of high tides and storm surges.

The report has new findings compared to State of the Climate 2014.

Significantly, we report that warming in the global oceans now extends to at least 2,000 metres below the surface. These observations are made possible by the Argo array of global floats that has been monitoring ocean temperatures over the past decade. When we talk about the climate system continuing to warm in response to historical greenhouse gas emissions, that is almost entirely due to ongoing ocean warming, which these observations show is now steadily in train.

The other new inclusion is the science of extreme event attribution.

In the past five years, an increasing number of studies, using both statistical and modelling techniques, have quantified the role of global warming in individual extreme events. This complements previous science which partly attributes a change in the frequency of extreme weather, such as an increase in the number of heatwaves, to global warming.

In Australia, this includes studies that used the Bureau’s Predictive Ocean Atmosphere Model for Australia (POAMA) to essentially predict observed extreme events in a modelled climate with and without an enhanced greenhouse effect.

In particular, studies of record heat experienced during Spring in 2013 and 2014 have shown that the observed high temperatures received an extra contribution from background global warming.

These studies are an initial step towards understanding how climate change could affect the dynamics of the climate and weather system. In turn, this work provides greater intelligence for those managing climate risks.

This article was first published at The Conversation.

Related content