State of the Climate 2018 is the latest biennial snapshot of climate change in Australia. It focuses on observed long-term trends that are happening now and are likely to continue into the near future, as well as significant climate events that have occurred over the past two years.

State of the Climate 2018 is the latest biennial snapshot of climate change in Australia. It focuses on observed long-term trends that are happening now and are likely to continue into the near future, as well as significant climate events that have occurred over the past two years.

These changes are described through the latest observations from CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology marine, atmospheric and terrestrial monitoring programs.

The report also summarises the latest climate research from Australia and around the world. This will help inform a range of economic, environmental and social risk assessments and responses by government, industry and communities.

Multiple lines of evidence show the climate system changing in ways that are discernible from natural variability, and consistent with a human influence on climate. These changes are having an impact on our natural and built environment.

In particular, climate change is being felt through an increase in the frequency and severity of high-impact weather events such as heatwaves, extreme fire weather conditions, coastal inundation and marine heatwaves. These trends are projected to continue.

Some of the report’s major findings are described below.

Australia’s average air temperature has warmed by just over 1℃ since national records began in 1910. Oceans around Australia have also warmed by around 1℃ since 1910.

Atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide are rising globally. Emissions from the burning of fossil fuels continue to increase, and are the main contributor to the rise in CO₂, with some contribution from changes in land use.

Atmospheric CO₂ concentrations measured at Cape Grim, Tasmania (one of three main global measuring stations, alongside Mauna Loa, Hawaii, and Nunavut, Canada), have persisted at levels above 400 parts per million (ppm) since 2016. What’s more, the combined concentration of all greenhouse gases exceeded the equivalent of 500 ppm CO₂ in mid-2018. These milestones haven’t been crossed for at least 800,000 years, and likely 2 million years.

Australia’s warming trend has led to an increase in the frequency of extreme heat events. For example, very high monthly maximum temperatures that used to occur around 2% of the time (based on the average for 1951–80) now happen about 12% of the time (2003–17).

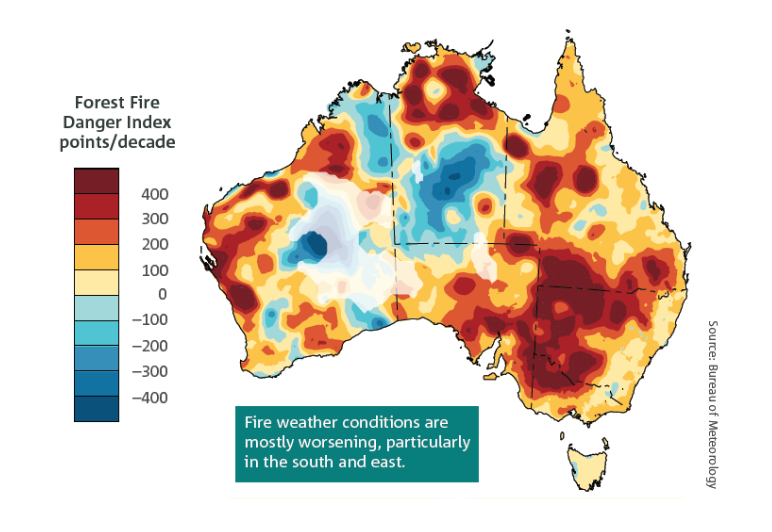

Other elements of Australia’s climate have also shown long-term changes. New analysis techniques now provide a more detailed picture of changes to fire weather through time. The annual total of daily values of the Forest Fire Danger Index is increasing over large areas of Australia. Most regions also saw an increase in the most extreme 10% of fire weather days, and fire seasons have lengthened.

Rainfall in April–October has been steadily decreasing in Western Australia’s Southwest, and has decreased since the 1990s in southeast Australia. In contrast, rainfall has increased in parts of northern Australia since the 1970s.

The observed long-term reduction in rainfall across southern Australia has led to even greater reductions in streamflow. Long-term average streamflow has decreased in most regions of southern Australia, and increased in regions of northern Australia.

A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, and this is an important driver of the observed increase in the intensity of short-duration rainfall, sometimes linked to flash flooding. Southern Australia is projected to experience decreases in average rainfall and more time spent in drought. Meanwhile, most of the country can expect an increase in rainfall intensity.

Historically, significant weather and climate events are often the result of the combined influence of several extreme factors at once. Higher temperatures during periods of below-average rainfall, for instance, can exacerbate drought conditions. Temperature, dryness and wind come together to create dangerous bushfire conditions.

The warming in Australia’s oceans has contributed to longer and more frequent marine heatwaves – defined as periods when sea surface temperatures are much warmer than average. The world’s oceans are a crucial moderator of the climate, taking up more than 90% of the extra heat in the system – most of it is absorbed by the Southern Ocean.

Sea levels continue to rise through the combined effects of warming oceans and melting ice from land-based glaciers and ice sheets. Global average sea level has risen by more than 20cm since 1880, but the rate varies from place to place. About 25% of the CO₂ emitted by human activity diffuses into the oceans, making them more acidic in the process.

The past two years, 2016 and 2017, have seen back-to-back bleaching events in parts of the Great Barrier Reef, linked to marine heatwave events. These changes are very likely linked to warming oceans, and primarily driven by the human influence on the climate.

Well-established scientific theory and climate model studies both show that the warming would largely not have occurred without the increase in greenhouse gas concentrations. In addition, the current increase in temperatures accords with projections made nearly 30 years ago. Warming is projected to continue into the future as the effect of past emissions continue, and more greenhouse gases are emitted. Australia is projected to experience increases in sea and air temperatures, with more hot days and marine heatwaves, and fewer cool extremes.

It takes time for the climate system to warm in response to increases in greenhouse gases, and the historical emissions over the past century have locked in some warming over the next two decades, regardless of any changes we might make to global emissions in that period. However, by the mid-21st century, higher ongoing emissions of greenhouse gases will lead to greater warming and associated impacts, and reducing emissions will lead to less warming and fewer associated impacts.