Australians visiting Centrelink offices waited 30% longer on average in the past financial year compared with 2015-16, as the agency continues to shut or merge shopfronts.

The figures include the first half of 2020, in which the unemployment rate spiked due to the coronavirus pandemic resulting in hundreds of thousands of people queuing outside Centrelink offices.

However, even with this increase in people attending Centrelink in person, almost all Centrelink offices had fewer people through the doors in 2019-20 compared with four years earlier, when waiting times were lower.

With Services Australia pushing customers towards online services such as the MyGov app, a Guardian Australia analysis reveals 87% of the agency’s offices have seen their waiting times blow out over the past four years.

The analysis compares site-by-site statistics from the past financial year to 2015-16, the last time such detailed figures were reported to the Senate.

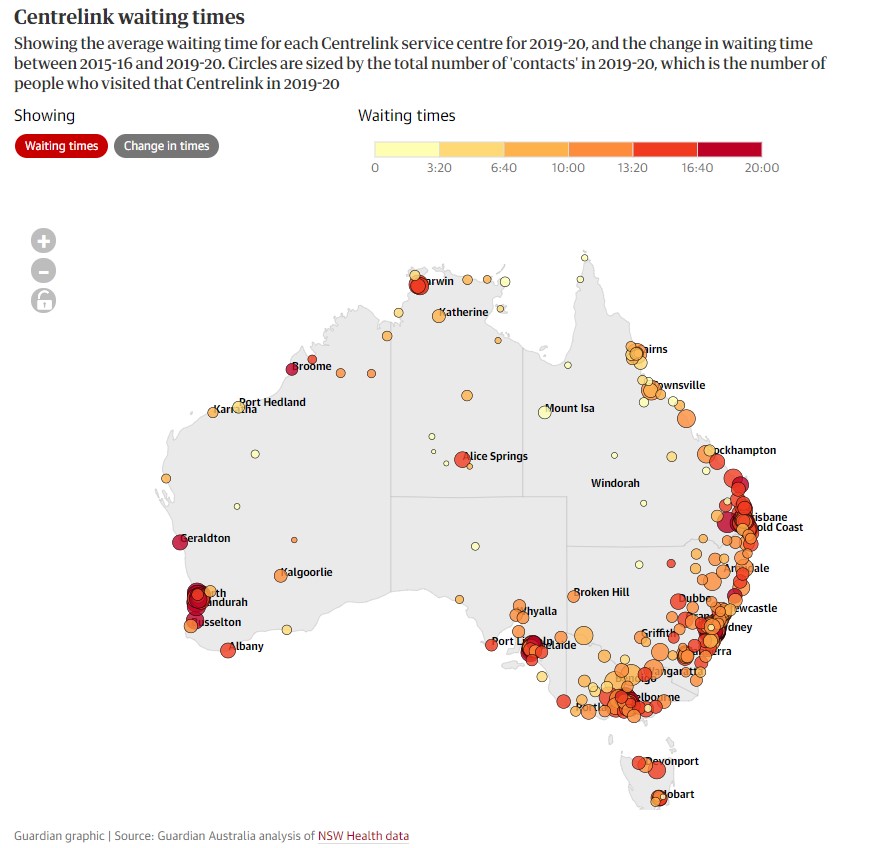

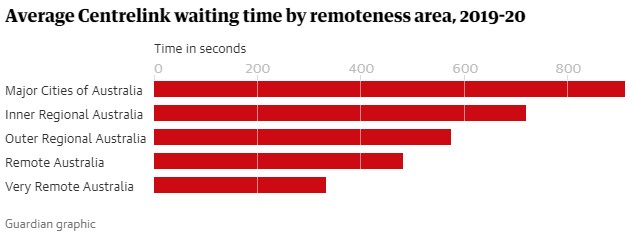

The analysis reveals people living in major cities waited about five minutes longer on average than 2015-16, while those in regional centres spent about four minutes longer waiting for help.

Overall, Services Australia’s figures show the average waiting time in 2019-20 was about 14 minutes, up from about 11 minutes in 2015-16. The figure is an improvement from 2018-19 and within the agency’s targets.

But Guardian Australia’s analysis shows waiting times have ballooned across the offices since 2015-16 despite a dramatic reduction in patronage. The data shows face-to-face contacts fell across 94% of all sites in 2019-20 compared to 2015-16.

While Services Australia rejected comparisons between the data, noting 2020 was a “year like no other”, the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) president, Alistair Waters, said staff cuts since 2013 meant it was “no surprise” wait times had increased. He accused of the government of ignoring the impact of service centre closures.

“An app or a crashing website won’t answer calls, or solve the long lines at service centres,” Waters said.

In the 12 months to 30 June 2020, which included the unprecedented demand seen at the start of the pandemic, Sydneysiders spent the most time waiting at a Centrelink office.

By patronage, the busiest service centres in Australia were the western Sydney offices of Liverpool, Fairfield and Blacktown, followed by Sunshine in Melbourne’s west.

Sydney had the longest average waiting times with Chatswood (25.32 minutes) closely followed by offices in Darlinghurst (24.51) and Ingleburn (24.32) close behind. In Chatswood, residents waited 13 minutes longer on average than they did in 2015-16.

Eight of the 10 offices with the longest average waiting periods were in Sydney, followed by Rockingham south of Perth (21.16) and Modbury in Adelaide (20.55).

Throughout 2019-20, Australians could expect to wait longer than 15 minutes at 82 Centrelink offices across Australia. In 2015-16, that was true of only 11 sites.

The new figures come as the agency shifts towards digital services, a move that’s been further accelerated by the pandemic.

Services Australia’s past annual reports show the number of Centrelink offices had fallen to 326 in 2019-20, a reduction of 24 since 2015-16.

The agency came under fire in March when a boost to welfare benefits and mass layoffs led to enormous lines outside Centrelink offices.

In response, the agency directed all but the most vulnerable customers to file their claims online and employed a surge workforce, though some of those temporary staff are now being laid off.

Cassandra Goldie, the Australian Council of Social Service chief executive, said it was vital the government ensured adequate face-to-face services.

“We welcomed the additional staffing of Centrelink to respond to the crisis,” she said.

“However, we need to ensure that numbers of permanent staff at Centrelink are boosted to meet need. Not everyone can access services online, and face-to-face human services continue to be essential for many accessing income support, including older people, people with lower literacy skills, people from diverse backgrounds and people with disability.”

In the first three months since July, the number of contacts and average waiting times are down significantly, likely as a result of the pandemic. The agency’s annual report notes that in April, May and June demand at Centrelink offices was down 40% compared with 2019.

The agency recently backflipped on a controversial move to close an office at Abbotsford in inner Melbourne, which was among those that received an influx of requests for help in late March.

Like most, that office has seen reduced demand since 2015-16, though there were still a total of 51,148 contacts from customers in the past financial year.

An office at Newport in Melbourne’s west closed in December last year. Services Australia has denied reports another closure is planned at Tweed Heads on the NSW-Queensland border.

Another planned closure at Mornington, in cabinet minister Greg Hunt’s Melbourne electorate of Flinders, has been postponed to March 2021. The site received 31,000 contacts in 2019-20.

Federal Labor’s government services spokesman, Bill Shorten, said the Coalition had combined a “slash and burn with aggressively trying to push everyone on to the app”.

Hank Jongen, Services Australia’s spokesman, said it was “not possible to draw comparisons” between the data because 2020 was “a year like no other for Services Australia”. He noted during the pandemic “wait times averaged less than five minutes from July to September”.

“In 2015 it was common for people to queue at service centres to update their address details, claim a Medicare payment or update their income or assets,” Jongen said.

“Today, all major claims are now online, including 99% of Medicare transactions, and we have simplified the claims process. This means the customers we’re more likely to see in our offices are those with more complex circumstances, such as losing their job, facing homelessness or fleeing domestic violence.”

Jongen said changes to the way the agency collected data in 2017 had also resulted in more accurate measurements and an overall increase in the wait times.